Micah Perks recommends books about women who refuse to conform to societal norms

Originally, weird came from the Old English wyrd, meaning fate. Wyrd went out of use in English until Shakespeare brought it back to describe his weird sister witches in Macbeth, perhaps also referencing the three mythological goddesses, the fates, who control destiny. Thus, we arrive at the five W’s — Weird — Witch — Women — Writing that’s Wrong. In Joanna Russ’ satiric guide to How to Suppress Women’s Writing, number eight is “anomalousness: assert that the woman in question is eccentric or atypical.”

I think it’s time to embrace the anomalousness, insist on its strength. I like the idea of a weird sisterhood with powers to see beyond the ordinary. Weird sisters stirring a pot of who knows what. Weird books are my favorite kind of books, anyway: books that are unclassifiable, books that value surprise, the tangent, books about women and girls who refuse to conform to societal norms. I’m talking about weirding gender roles and the domestic space. Books that are non-judgmental, irreverent, about women and girls who are a little amoral; a book where laughter sits so close to grief and horror that it makes them uncomfortable. A book that exposes the essential weirdness of existence.

I know the U.K. has lately gotten all Brexit-y with the rise of populism, but the U.K. in my head is populated by witchy women in unravelling sweaters, putting kettles on to boil and spreading marmite on toast, mumbling wyrd prophecies. (This could be because my father is a retired British butler with long white hair who likes to stroll around his property wrapped in a bear skin, his overfed pug by his side. He is definitely a weird sister.)

Here are a list of British authors that celebrate weird women. As Shakespeare’s witches said, “Come sisters…show the best of our delights.”

Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner

Published in 1926, Lolly Willowes starts out with a classic Jane Austen Sense and Sensibility-like set up — a single young lady is kicked off the family estate when her father dies and must move in with her brother’s family, where she’s treated as a drudge. At first, Lolly does not seem weird at all. The novel clips along in a realistic vein until one day, the now middle-aged Lolly is in a shop and, without warning, she has an ecstatic vision,“she felt as if she had woken unchanged from a twenty-year slumber.” Suddenly, Lolly becomes completely unmanageable. The novel goes off its realistic rails. Magic happens. Witches. After escaping her domestic captivity, Lolly decides, “it is best as one grows older to strip oneself of possessions, to shed oneself downward like a tree, to be almost wholly earth before one dies.” Sylvia Townsend Warner, who was also a painter, refused to stay in her genre lane: she also wrote, amongst others, The Corner that Held Them, a novel about a twelfth century convent and a series of interlocking tales about fairies, Kingdoms of Elfin.

The Fountain Overflows by Rebecca West

Andrea Barrett writes in her introduction to The Fountain Overflows, first published in 1956, “I have loved this novel for over a decade without being able to explain exactly why.” That is the definition of the weird. The Fountain Overflows is about an artistic family of women dependent on an undependable father. The book has a smooth surface, but all the women, especially the mother, Mrs. Aubrey, say the oddest and most profound things. Perhaps because, as it turns out, they can read minds. Of Mrs. Aubrey we learn, “she understood children, and knew that they were adults handicapped by a humiliating disguise and had their adult qualities within them.” Cousin Rosamund is tormented by a poltergeist. There is something about the tension between the intimacy and alienation in this family of unexpected women that undoes me, that reveals the great longing to be together along with the great longing to escape at the strange heart of every family.

Gertrude’s Child by Richard Hughes

I first encountered the Welsh writer Richard Hughes when I read Gertrude’s Child as a kid. Gertrude is an exasperated wooden doll who marches stiffly away from her owner, buys herself a little girl, and then leaves her out in the rain while she takes tea with some random stuffed animals. It’s the height of weird, the gloriously hard heart of the independent doll, the pathetic child without enough sense to come in out of the rain. I adored it.

A High Wind in Jamaica by Richard Hughes

In A High Wind in Jamaica, published in 1929, some rich kids are captured by pirates, but in a similar inversion to Gertrude’s Child, the kids turn out to be more terrifying than the pirates, especially murderous little Emily. A High Wind in Jamaica pretends to be a child’s adventure story, but it’s really a book for adults about the nature of little girls, or perhaps all our natures, in the vein of Lord of The Flies, but more charming, funnier, and, of course, weirder.

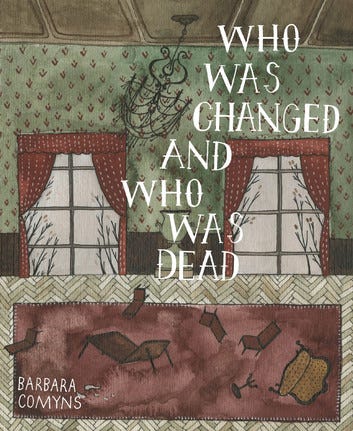

Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead by Barbara Comyns

The fabulously quirky Dorothy Project republished this 1956 novel about a quaint English village ravaged by flood and a mysterious disease. It begins the morning after the flood: Eben Willoweed jauntily “rowed his daughters around the submerged garden” amongst drowned animals. Comyns continually creates odd juxtapositions and undercuts her characters at every turn. “Grandmother Willoweed had raved and moaned and torn her hair, although she was already rather short of it.” When one of the characters finally escapes the disaster-ridden village and her absurd family to become “completely civilized,” I felt relieved for her but also regretful that she’d become an ordinary woman. Barbara Comyns was a true eccentric herself, an artist who bred poodles and fixed pianos for a living, and who had relationships with first an artist, then a criminal and finally a civil servant. Spoiler alert: her novel The Vet’s Daughter involves revenge by levitation.

Feminist Retellings of ‘Dude’ Books

Like a Mule Bringing Ice Cream to the Sun by Sarah Ladipo Manyika

Sarah Ladipo Manyika created an unconventional heroine and gave her book the weirdest title ever. Her novel, first published by Cassava Republic Press in London and Nigeria, was shortlisted for the 2016 Goldsmiths Prize for fiction that “breaks the mould.” The book is about a seventy-five-year old Nigerian American woman in San Francisco, “a city where people take their kids to school in their pajamas.” Dr. Morayo Da Silva, lover of books, the kind of woman who spontaneously buys two bouquets of tulips instead of one, flirtatious, wise, indomitable, is at the heart of this surprising, pleasure-driven novel that quietly subverts literary conventions about whose lives are worthy of literature.

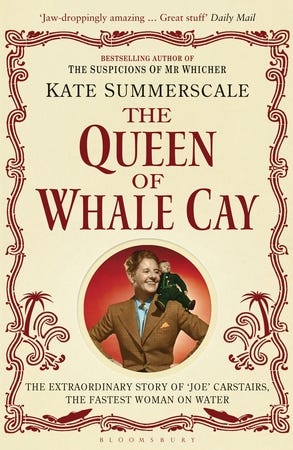

The Queen of Whale Cay by Kate Summerscale

Summerscale is best known for her book The Suspicions of Mr Whicher, an addictive mixture of true crime and social history that was made into a BBC series. The Queen of Whale Cay is a biography of the truly extraordinarily eccentric life of Marion “Joe” Carstairs. Cartstairs raced speed boats in the 20’s, cross-dressed, smoked cigars, had affairs with Marlene Deitrich and Oscar Wilde’s niece, and then in the ‘30s bought an island in the Bahamas and became its mostly benevolent “Queen.” Oh, and she also spent her life obsessed with a leather doll she named Lord Todd Wadley. Summerscale is a brilliant researcher and writer, with an eye for the weird and telling detail. I won’t soon forget the image of Queen Joe riding around her island on her motorcycle with her doll strapped behind her.

About the Author

Micah Perks’ fourth book, a collection of linked short stories, True Love and Other Dreams of Miraculous Escape, came out in October. More info and work at micahperks.com

7 British Books that Celebrate Weird Women was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.