What is a desert? A desert is a place with little rain, a dry place where plants struggle, where animals struggle, and only those creatures who have adapted themselves to the harsh winds and sun can survive. A desert is extremely hot, but it can also be stunningly cold, like Antarctica—a desert of ice and snow. A desert is expansive and flat with waves of inhospitable sand. A desert is a landscape of corals and reds, with mountains that touch the clouds and air that sings ancient songs. A desert can seem so very old, primordial even, a place before people, designed without people in mind. But many deserts are relatively young and often have been created, unintentionally, by us. A desert is wise. A desert is mute. A desert is the place we’re supposed to go to find our true selves. A desert is not a place at all, but rather a state of mind. It is pure spirit, the soul confronting itself in silence. It is a place to experience the body’s fragility and its dependency on water and food. A place of wandering; a place of finding. A place of strife; a place of peace.

Growing up in Las Vegas, Nevada, a city of sparkles in sand, I was taught to see the desert as barren and useful only as a vessel in which to fulfill the ambitions of men. Contrast that with the following thought by the poet Joy Harjo: “I don’t see the desert as barren at all. I see it as full and ripe… it does with what it has, and creates amazing beauty.” Perhaps how one experiences the desert depends upon whether you see it as empty or full, and how you act in the face of that “presence” or “absence.”

The following books explore aspects of the desert, specifically as experienced by women—women singing the desert, women lost in the desert, women looking, women drowning, women showing. “[He] did not understand,” wrote Mary Austin in the story collection Lost Borders of a minister who has newly arrived to her desert from the East Coast, “that the desert is to be dealt with as a woman and a wanton; he was thinking of it as a place on the map.“

Secrets from the Center of the World by Joy Harjo, photography by Stephen E. Strom

In the work of poet Joy Harjo, desert is a verb. It is an act, a ceremony—an ancient mountain lion shifting his bones; an old man who wakes and prays then comes inside to cook his breakfast; the shutting of a car door that echoes into the dark of the mesa west. The desert is a “pure event,” but one “mixed with water, occurring in time and space, as sheep, a few goats, graze, keep watch nearby.”

Written in collaboration with the photographs of astronomer Stephen Strom, Secrets From the Center of the World begins with the words, “All landscapes have a history.” The desert holds something of the pure spirit that so many have written of, but for Harjo—current U.S. Poet Laureate and first Native American to hold the position—this spirit is inextricable from stories. The stories are of the people who live, or have lived, in the desert, but they are also stories of the desert itself. “There are voices inside rocks,” writes Harjo in the preface, “they are not silent.” The desert, which looks so deceptively still, is actually filled with motion and time. It is not the desert, therefore, that brings stillness and silence to us. The desert is an invitation to become silent so that we might hear its tales. For Harjo, the desert is fat and abundant with desert stories, which include stories of trauma and grief. The desert gives as much as it takes, and can teach us how to sing its song, even if it’s a song we don’t know, and maybe, do not want to know.

Lost Borders by Mary Hunter Austin

Though she was born in Illinois, and spent a number of her years in New York and Europe, Mary Hunter Austin is a writer of the American West. Moving to California in 1888, Austin’s adult life was largely spent in deep communion with the people and landscapes of the Mojave Desert and New Mexico. A feminist, socialist, mystic and escaped Midwesterner, Austin’s desert could be put in the category of “desert as freedom.” But more than that, I think Austin was seeking something she calls “pure desertness,” a desire to know something essential in the desert, a message, one Austin learned largely through the act of seeing.

In Lost Borders, as in most of her works, Austin’s writing unfolds in snapshots: “a crumbling tunnel, a ruined smelter, and a row of sun-warped cabins under tall, skeleton-white cliffs.” Straight, white, blinding, flat, forsaken. Starved knees of hills and black clots of pines—the way a certain part of the desert looks can teach you its lesson, though that lesson, like the land that tells it, might be one of hazy borders and sandy edges. More than once in Lost Borders, Austin begins a tale that seems to evaporate just before it ends, like an unraveled ball of string that leaves no center. “There was a woman once at Agua Hedionda—but you wouldn’t believe that either.” This is the desert too, for Austin, a place not just of lost borders but a place that has no end, and thus, fewer limits.

In Lost Borders, Austin also conjures a quality of the desert not often described: the land’s sensuality, and even its femininity. “If the desert were a woman”, she wrote, “I know well what like she would be: deep-breasted, broad in the hips, tawny, with tawny hair, great masses of it lying smooth along her perfect curves…eyes sane and steady as the polished jewel of her skies…such a largeness to her mind as should make their sins of no account, passionate but not necessitous, patient—and you could not move her, no, not if you had all the earth to give…If you cut very deeply into any soul that has the mark of the land upon it, you find such qualities as these—as I shall presently prove to you.”

Everybody Needs a Rock by Byrd Baylor, illustrated by Peter Parnall

This is a profound book in the guise of a light children’s book. It makes one important point: Everyone needs a rock. The book offers ten helpful rules on just how to obtain your very own special rock including, “Don’t let anyone talk to you while you’re looking for your rock,” “Don’t worry while looking for your rock,” “Don’t get a rock that is too big or too small,” and “You must get truly all the way down on the ground to look at all the rocks in the eye in order to find the one for you.” Baylor’s little book creates a sensory experience of the desert by inverting its landscape and shrinking it into what you might call the micro-sublime. One must not just look at rocks en masse, as many do; you must find your individual rock by smelling it, stroking it, listening to it. Through your rock, you can share an intimacy with the desert landscape and perceive prehistory in your hand. Also, by the end of your search, you will have a rock friend that will last for a million years. Baylor’s desert is a site of curiosity and discovery—a place, even, for play. Why not? Yes, there is the overwhelming spread of the desert with its dizzying lack of corners and shifting landmarks. And also, there is just this rock, your rock, should you choose to find it.

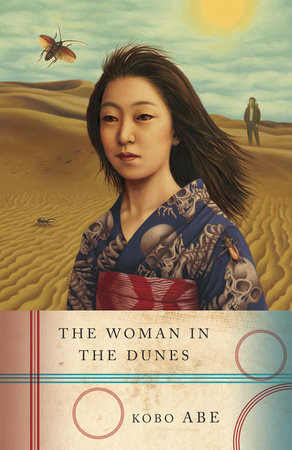

The Woman in the Dunes by Kōbō Abe

One day, a man on a short holiday goes looking for insects in a remote village in Japan, built among the dunes. The man is a collector and, as all collectors, eventually loses track of time in the dizzying landscape of sand. He asks a local villager if he might stay somewhere for the night, and is led to the home of a woman whose little shack is at the bottom of a deep hole in the dunes. Thinking he is to be there one night, the man soon realizes that he has been tricked into living with the woman in perpetuity and for one purpose: to help her with the daily work of digging sand that constantly threatens to drown the little shack—and in fact the entire village.

As you can imagine, the man thinks only of how he can escape this wretched life of repetitive, pointless, Sisyphean labor. The story is told through the man’s desperate and winding series of thoughts, but it is the woman, I believe, who is the book’s true focus. The Japanese title of this book, Suna no Onna, translates as Sand Woman. The man is dumbfounded by the woman’s seeming passivity and even stupidity, and by her lack of desire to escape what he sees as a life of thankless slavery. Yet the woman, while not exactly happy, seems quite content with her life.

The Woman in the Dunes is an extended meditation on the elemental power of sand. While the man sees this power as a force to fight against, the woman appears to see the act of clearing sand as simply her life’s work. She approaches this task with a Zen-like concentration. Is the woman just a sacrifice, as the man thinks, an offering to the villagers or even the gods of sand? Or is she free from the bonds of “self?” Just as one’s footsteps are immediately effaced in sand, so can the desert erase one’s individuality. Whether you think of this as liberation or hell is up to you.

Stories of the Sahara by Sanmao

Can you remember a time when “the world” came to us in encyclopedias and books and guides? This is how the writer Sanmao first discovered the Western Sahara, while absentmindedly flipping through the pages of a National Geographic in an apartment in Madrid. Chinese-born and raised in Taiwan before living for a time in Spain and Germany, Sanmao didn’t know where she belonged. But looking at the shiny magazine pictures of the Sahara, she was at once seized with a feeling of homesickness and longing she couldn’t quite understand, and this longing soon became obsession.

Sanmao did eventually travel to Spanish-colonized Western Sahara; her six years there living on the borderland between expats and Sahwari natives make up the tales in Stories of the Sahara. Residing in a rented house on the edge of town, Sanmao is ever asking the locals how one gets into the desert. But, this is the desert right here, they reply. You are in it. Living on the edge of desert and town, Sanmao’s writings invoke the question: Where does the true desert begin? Is there a real desert that can tell us the secrets of life? Her ideas about the desert—romantic and childish, by her own description—are forever bumping up against its troubles: djinns that howl in the night, goats that fall from the sky, neighbors who steal your shoes. But for Sanmao, a true romantic, even these experiences—by turns annoying and terrifying—are woven into the desert’s magic.

Written in the 1970s, Sanmao’s portrait of the desert is an ancient one; it is a place of “poetic desolation,” the “boundless” place in which to expand one’s personality and move beyond one’s own individual borders. Sanmao is the desert traveler as seeker, the desert a destination for those who don’t quite fit into the life prescribed for them, who feel like strangers on earth.

Revolt Against the Sun by Nazik Al-Malaʾika, translated by Emily Drumsta

Born in 1920’s Baghdad, the poet and critic Nazik al-Mala’ika left Iraq in 1970 after the rise of the Ba’ath Party. She lived in self-imposed exile in Kuwait and Egypt until her death in 2007. Al-Mala’ika is known as a pioneer of Arabic free verse (taf‘ila poetry) but her work has been largely untranslated; the soon-to-be-published Revolt Against the Sun: A Bilingual Reader of Nazik al-Mala’ika’s Poetry is the first major edition of her work in English.

Although al-Mala’ika is considered an innovator of modernist verse, she is also fundamentally a Romantic, and, as her translator Emily Drumsta has written, al-Mala’ika’s poetry articulates deeply felt emotions and sensations through the use of traditionally romantic motifs—primarily the sun. Yet, while for European Romantic poets—living in darker, colder landscapes with seasons that have more obvious contours—the sun is a sign of hope and joy, in al-Mala’ika’s literature of the desert, the sun is portrayed as a judge, an oppressor bearing down on fragile hearts with its heat and blinding rays that leave no room for our innermost concerns. She writes, “I came to pour out my uncertainty / in nature, ‘midst sweet fragrances and shadows, / but you, Sun, mocked my sadness and my tears / and laughed, from up above, at all my sorrows.” In the desert, the sun creates thirst and cruelly rips off the shroud of dreams fashioned in the nighttime. In the desert, it is the light of the stars and not the sun that inspires the “hopeful heart”:

How often I have watched stars as they pass

letting the twilight shape my incantations,

and watched the moon bidding the night goodbye,

and roamed the valleys of imagination.

The silence sends a shiver through my spine

beneath the evening’s dome, so still and dark,

Light dances, painting on my eyelids with

The dreamy palette of a hopeful heart.

“And as for you, oh sun… what can I say?

What can my passion hope to find in you?

I Am the Beggar of the World: Landays from Contemporary Afghanistan translated by Eliza Griswold, photography by Seamus Murphy

In the winter of 2012, the poet Eliza Griswold, along with photographer Seamus Murphy, began collecting landays after learning the story of a teenage girl living in Afghanistan who was forbidden to write poems by her male family members, and set herself on fire in protest. A landay is an ancient oral poetic form created by (and are primarily for) Pashtun women living between Afghanistan and Pakistan. The two-line poems are anonymous, and as they can be swapped and sampled from each other, are also fundamentally authorless. Contemporary landays reference Google as much as goats, but are most often riffs on themes like love, war, family, and homeland.

When sisters sit together, they always praise their brothers.

When brothers sit together, they sell their sisters to others.

In the book’s introduction, Griswold writes that she wanted to collect landays before US troops pulled out of Afghanistan. Her fear—and the fear of many with whom she spoke—was that Pashtun women were living in a brief grey area of relative freedom, and that their lives would become smaller and more isolated, as they were during the reign of the Taliban, when American soldiers—who were resented as they were appreciated—left.

If you hide me from the Taliban,

I’ll become a tassel on your drum.

Once, landays were shared around campfires and sung in fields and at weddings—they were a form of community bonding as well as art. Now, they are just as often shared on Facebook and in text messages, but still battle cries against the social deserts that threaten us all. They are a secret language Pashtun women use to connect with each other in universal rage and grief and fear of violence, as well as humor and longing.

I’m in love! I won’t deny it, even if

you gouge out my green tattoos with a knife.

In my dream, I am the president.

When I awake, I am the beggar of the world.

The post 7 Books About Women in the Desert appeared first on Electric Literature.

Source : 7 Books About Women in the Desert