When I was growing up in West Virginia, I thought nobody wanted to read books set in my home of rural Appalachia. All the stories seemed to be about people in cities, living far more important and exciting lives. By the time I’d fallen in love with words enough to begin writing fiction, this lack of representation allowed a certain shame to settle in. A quiet voice telling me that my experiences didn’t matter. It took years, and several perspective altering books, to dispel those notions.

When I was writing The Poison Flood, a novel about a reclusive musician whose small West Virginia town is threatened by the environmental disaster of a toxic chemical spill, I was aware of the tremendous privilege and responsibility involved in writing a version of Appalachia that was nuanced, sympathetic and honest to my experience. Nearly twenty-five million people across thirteen states make up the region of Appalachia. That’s a lot of stories.

The following are some of my favorites:

Monsters in Appalachia by Sheryl Monks

The title may put readers in mind of West Virginia legends such as The Mothman or Flatwood’s Monster, but Sheryl Monk’s collection is largely based in stark realism. Only the title story, an apocalyptic fever dream where a woman and her husband catch and display monsters in a nightmare carnival might be considered speculative fiction or even horror. The monsters depicted here are often adults, either violent men like the outlaw brothers in “Justice Boys” who menace a lone mother trying to take her sick infant to the hospital or the disappointing father from “Little Miss Bobcat,” a standout story where an impoverish elementary school girl tries to save up enough money to win her school’s Little Miss Bobcat crown. Monk is often showing young women coming to terms with the disappointing nature of their elders. In “Barry Gibb is the Cutest Bee Gee” the jaded female relatives who sunbathe with the adolescent narrator try to instruct her in all the wrong ways about love. The book makes actual monsters seem less captivating than the flawed humans who are frightening in their commonplace inability to be kinder to one another.

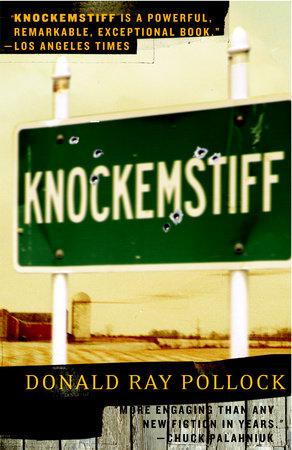

Knockemstiff by Donald Ray Pollock

I was an ambitious young writer trying to find the courage to send out my stories when I first read this collection. I’d never encountered anything like it, but neither had anyone else. By following a similar structure to connected works like Winnesburg, Ohio, or Olive Kitteridge, Pollock explores the desperate aspects of rural America from an insider’s point of view. There are many depraved moments, but even the most outrageous scenes manage to avoid the feeling of exploitation. Pollock’s characters often act in reprehensible ways, but there is empathy here for the young narrator of “Real Life” who only wanted to watch Godzilla at the drive-in but is forced to fight another boy by his father, the addicts searching for a fix in “Bactine,” the weightlifter pressured into using steroids by his abusive father in “Discipline” and the lovesick loner of the title story. Together, the tales weave a panoramic view of a community on the brink of collapse and those caught in the decline.

The Line That Held Us by David Joy

While poaching deer to keep meat in the freezer, Daryl Moody accidentally shoots and kills the brother of Dwayne Brewer, the dangerous antagonist of Joy’s novel. Joy uses this thriller premise to explore Appalachian people’s connection to the land and their loyalty to family and friends, even when that loyalty ruins all they strive for. The true revelation of the book is Dwayne Brewer, who despite being an obvious villain, Joy imbues with intelligence and a warped moral code created by years of injustice. In a world full of chaos, Dwayne believes a man must make his own brand of reason. Such a character might have been only brawn and menace. Instead, Joy writes an antagonist who philosophizes on the nature of evil, often choosing a wicked path while knowing he should act differently. Consider an early scene that introduces Dwayne drinking beers at the local Walmart. After watching a teenager abuse a younger boy, Dwayne follows the bully into the bathroom, makes him remove his new shoes at gunpoint and submerge them in shitty toilet water. This need to right the injustices of the world is Dwayne’s main motivation throughout the novel. If life had been a little less vicious, readers can speculate that Dwayne might have chosen a better path.

The Birds of Opulence by Crystal Wilkinson

Winner of The Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence and The Weatherford Award for Fiction, Crystal Wilkinson’s novel follows several generations of African American women living in Opulence, Kentucky from the 1960s through the 1990s. The novel is episodic in scope, each vignette a specific moment of importance in the Goode or Clark family’s story. While each chapter focuses on one individual, Wilkinson employs an omniscient narration that occasionally drifts about the scene allowing us brief access to many of the characters’ interior thoughts and emotions. In the hands of a lesser writer, this approach might keep the novel from feeling cohesive, but Wilkinson manages to make the moments of church dinners, births, love affairs and break-ups carry the same weight in fiction as they do in our everyday lives. The novel must be read for its sentences. Entrancing, lyrical and other adjectives often used to praise writing feel inadequate in expressing the captivating nature of Wilkinson’s prose.

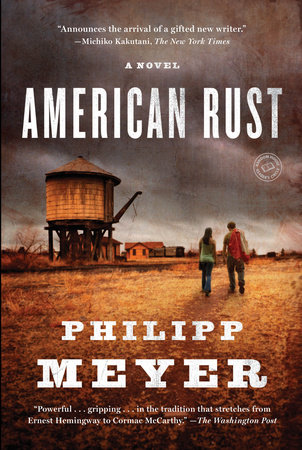

American Rust by Philipp Meyer

After missing out on college to take care of his ailing father, Isaac English decides to leave Buell, Pennsylvania, the fictional, economically destitute steel town Meyer uses to represent the very real parts of America abandoned by prosperity. Recruiting his best friend, Billy Poe, the two set out on a doomed exodus that is sidetracked by an act of violence. Meyer smoothly transitions to others in Buell like Chief Bud Harris, who is busy policing a town with increasing crime, and Isaac’s sister, Lee, currently attending Yale University and experiencing the uncomfortable truth that her birthplace will keep her from fitting into her new privileged environment. Those circulating the more prominent Isaac and Billy could feel like distracted digressions, but none of the large cast are underdeveloped. Written in a Modernist influenced stream of consciousness reminiscent of literary giants like Wolfe, Joyce, and Faulkner, Meyer’s prose never delves into imitation. Social class, masculinity, family obligation, and the other well-explored literary themes never feel tired. Frankly, it’s the sort of debut novel that makes other writers jealous.

Sugar Run by Mesha Maren

After nearly two decades in prison, 35-year-old Jodi McCarthy is released into a world she no longer recognizes. While on a trip to reconnect with the younger brother of a lost lover, Jodi meets Miranda Matheson, a struggling single mother fighting a former country music star for custody of their children. Jodi and Miranda’s romance sparks in barrooms and motels, but drab locales never detract from the moments of grace found in their connection. Maren, who spent years teaching creative writing at the Federal Prison Camp Alderson in West Virginia, understands the challenges Jodi experiences with sudden freedom. Whether it’s being overwhelmed by menu options at a Waffle House, or Jodi adjusting to having personal agency over where she travels, the novel shows real authenticity in these moments. With language as lush as the Appalachian landscape, it’s a profoundly engaging book.

Serena by Ron Rash

In his most well-known and powerful novel, Rash introduces readers to Serena Pemberton, the vengeful wife of a 1930s North Carolina lumber baron. Serena is both intelligent and rattlesnake cold from the earliest pages where she witnesses her husband kill the father of Rachel Harmon, a young woman he’s impregnated during his short time in the country. Throughout the novel, Serena holds an almost supernatural sway over the land, its animals, and the men of the lumber camp, yet patriarchal values stifle her ambitions. Eventually, jealousy turns Serena’s aggression toward Rachel and her husband’s illegitimate child. The historical narrative deals heavily in these themes of revenge, oppression, and class warfare while bravely allowing Serena to be a multifaceted, yet unlikable protagonist. It also contains a brilliant conclusion that feels both unexpected and inevitable.

The post 7 Books About Love, Belonging, and Community in Appalachia appeared first on Electric Literature.

Source : 7 Books About Love, Belonging, and Community in Appalachia