In my novel, Catch the Rabbit, I have tried to write about that hazy landscape made up of words and nothing more, which we call our past.

It is a very fragile thing so the writer has to support it with the iron scaffolding of fiction. In the end, the scaffolding might be the only thing that’s left, but its shape might tell us some little truth about what is left behind.

I wanted to find such a shape for what I consider my country: Bosnia—a place where several versions of the past exist simultaneously and seem to clash every 50 years only to create new pasts. I was not interested in what any one of you might easily find on Wikipedia—information about the physical place—but rather what stays within us after we abandon our home and our language.

Memories: From Moscow to the Black Sea by Teffi, translated by Robert Chandler

In 1918, Nadezhda Alexandrovna Lokhvitskaya leaves Moscow for what was supposed to be a short book tour in Ukraine. However, the famous Russian humorist will never return to her motherland as the news of censored artists and murdered colleagues reach her on the way. Narrated with refreshing humor so rarely found in stories of exile, Memories is not only an account of an artist disenchanted with Bolshevism, but also a beautiful eulogy to the lost ideals of youth. What I loved about this book was how precise it is in its portrayal of war as sheer madness, which always starts with a loud philosopher and ends with a pile of corpses.

Where You Come From by Saša Stanišić

I’m really trying to sound eloquent in this article, as eloquent as a non-native speaker can pretend to be, but the only thing I want to say when it comes to this title is I LOVE THIS BOOK. Not only because it tackles issues so close to my heart—Bosnia and its never-healing wounds—but because of the way it does so, questioning language, memories and the power of fiction to preserve both. The narrator leaves his hometown of Višegrad as a teenager and moves with his parents to Germany. As he is struggling to build a new identity in a new language, his beloved grandmother back home is losing hers to dementia. The magical last chapters turn this beautifully woven bildungsroman into an emotional gamebook, thus offering both the reader and the narrator an escape from death and oblivion—a superpower which only storytelling can generate.

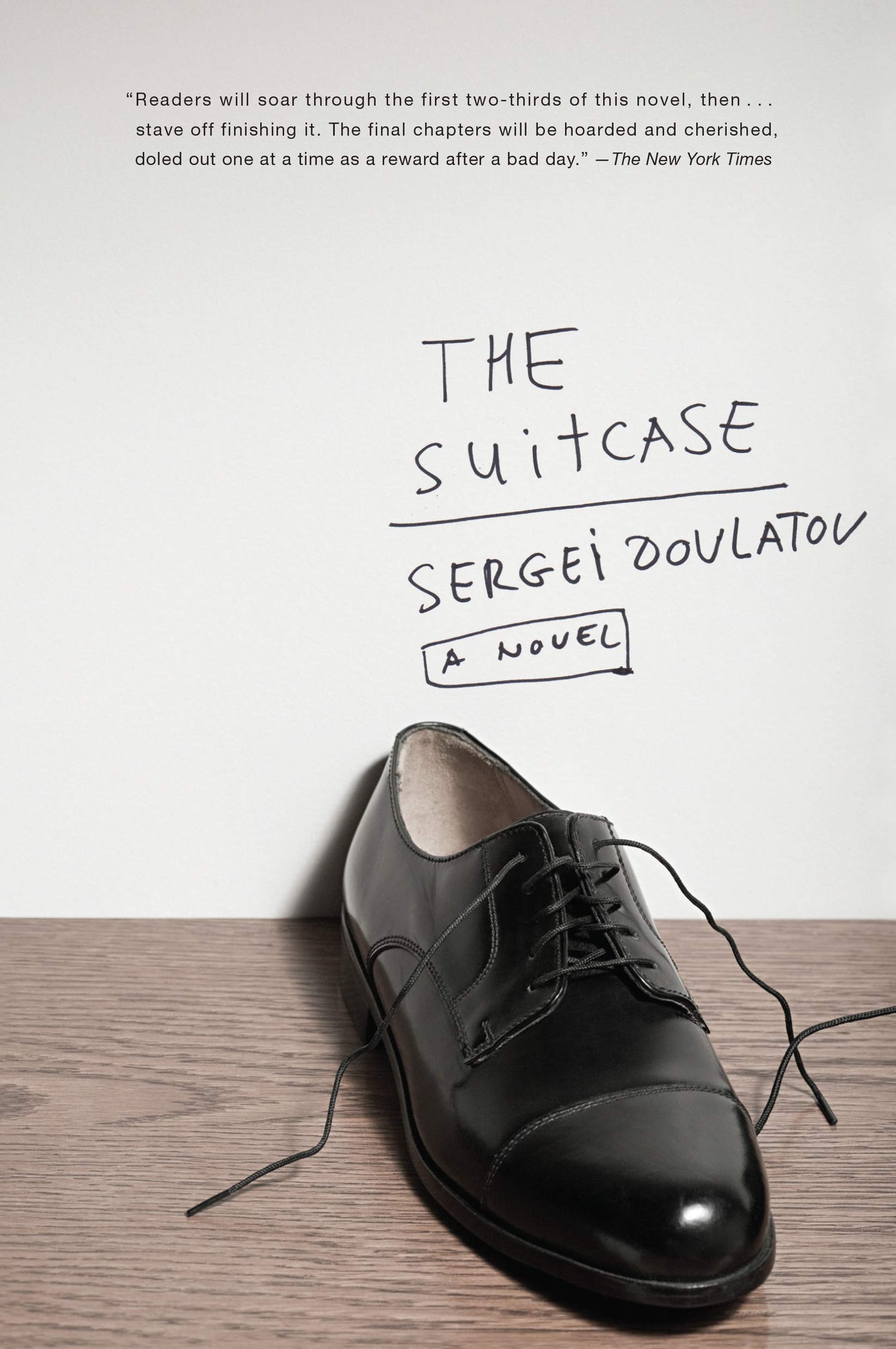

The Suitcase by Sergei Dovlatov, translated by Antonina W. Bouis

This wonderful novel is, indeed, a suitcase packed with the stories of eight items that the author brought to the US in 1978 when he fled the USSR. It is an account of exile as an ongoing exercise in storytelling—what is left behind is turned into memories through the alchemy of language alone. It is not in human nature to leave one’s home, yet leaving is what can make us see beyond the confines of one context. The very few objects we choose to take along are usually of no great objective value. It is the story that makes them precious and thus transforms them into little vessels of time lost. Dovlatov doesn’t do nostalgia, nor does he indulge in futile lament – he looks at the human condition with heart, humor and honesty.

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender by Dubravka Ugresic, translated by Celia Hawkesworth

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender is a novel that starts as an essay and turns into a masterly intricate mosaic made up of bits and pieces of different moments, memories, and lives. It is, among other things, a story of exile and the paralytic forces of nostalgia. But although Ugrešić is a writer of great stories, it is her acute awareness of form that makes her stand above her contemporaries. She questions exile as a narrative genre that cannot be shoved into a linear cause-and-effect chronology told from a single all-knowing perspective. The very condition of exile is one of fragmentation, and it is precisely by refusing the position of the novelist-in-charge that Ugrešić manages to truthfully portray this persistent liminality. Read her, and read her again.

A Novel of London by Miloš Crnjanski, translated by Will Firth

I want to try and persuade everyone to read a very sad 600-page book. You can thank me later. It is the forgotten masterpiece of European modernism, written by our greatest poet in exile and translated into English only last year. It tells the story of a married couple, Repnin and Nadia, two Russians exiled in London. The neighbors don’t speak their language and often think the couple is fighting, whereas—as the narrator puts it—we simply loved each other in Russian. Repnin, carrying the heavy tag of a displaced person, is struggling to obtain a work permit, while his wife learns to sew and tries to sell her dolls to Londoners. In one of the many heart-wrenching passages of the book, the fate of these dolls beautifully mirrors that of exiled Eastern Europeans at the dawn of capitalism:

“He knew that those dolls—rustic, Russian, and primitive—were being bought less and less, although they were colorful and pretty. New, lovelier dolls, more attractive for children, had begun to arrive from Germany and Italy, although they were products from former enemy countries. Now the war was over, and dolls were in demand. The American ones were even able to say: momma, mommy!”

Not available in English

I’m Not Going Anywhere by Rumena Bužarovska

You want to learn about the Balkans? You can’t. It’s vast, it’s complex, it’s deeply unreliable, and only exists in the many different versions of its own fairytale. But luckily for us there is literature—some of it exceptional—and through it, you can at least follow a few threads of the complex tapestry known as the post-Yugoslav condition. Nobody does it like Bužarovska—her short stories depict the social paralysis of post-transition North Macedonia with precision and simplicity so rarely found in contemporary post-Yugoslav literature. Her characters are stuck inside their own logic – even those who have managed to leave the Balkans physically, are never truly free of its influence. The humor is found in their unawareness of the petty patterns their lives follow, but the author is not a judge here, only a master observer of her own society. This collection is a true literary gem and I hope English readers will soon be able to enjoy it as well.

This Time Now by Semezdin Mehmedinović

By now it must have become apparent that I am using this article for shameless Yugoslav propaganda, furthering my agenda of making everyone read our literature. Because you should.

Because it’s really good.

Sem—and I am privileged to get to call him by that name—is one of my favorite living Bosnian authors. Perhaps this feeling is made stronger by the fact that we share a mutual obsession—the question of time and how to narrate it. On its surface, this remarkable novel tells the story of leaving and coming back, but its real power lies in the in-between—all that which is lost, remembered, fabricated, regained, and sometimes lost again. The Sarajevo of this book is perhaps the closest a contemporary writer has come to depicting the pain, the elusiveness, and the unyielding beauty of that city.

The post 7 Books About Exile and What We Leave Behind appeared first on Electric Literature.