When I first started working on this list, I didn’t have a list of titles so much as I had a list of problems that would make it very difficult to cobble one together.

Firstly, while Malaysia doesn’t lack for women writers, but most write in local languages—Malay, Tamil, Mandarin—many works remain inaccessible to English-language speakers, and thus, the world. The second issue is economic: because Malaysia’s small industry is reliant on the sales of educational textbooks, there is little room for non-fiction, let alone fiction. To hedge their bets, publishers tend to prioritize work by writers with established followings (i.e. prominent politicians, pugilistic journalists, rich businessmen) most of whom are men—and so we have our third problem, systemic sexism.

The lack of opportunity in local and international traditional publishing has enabled the flourishing of an indie scene. These indies and a persistent (if not robust) self-publishing industry have surfaced some of our most important women writers like Shih-Li Kow and Chuah Guat Eng—but it’s not enough. Many women writers publish as part of anthologies, but most never go on to produce book-length works. And the danger of going the route of indies and self-publishing is that there are many books that will never exist beyond the first print run. I will always mourn the loss of Dina Zaman’s seminal work, I Am Muslim, more or less impossible to find these days.

So no, I was not optimistic going into this. But when I began to really look, I was surprised by what I found. There are bold adventures, political mysteries, and stories about our uneasy cohabitation with the supernatural. Many experiment with the boundaries of genre, and span a range of mediums, perspectives and styles. There are books based in Malaysia, abroad, and beyond. All were written within the last 10 years, and eschew the colonial fictions that tend to sell well on the international market.

The thing is that colonial stories are expected of our writers—but while colonial history is important, it is not our only history. In many ways, our fixation with the past belies an inability to reckon with it, and doing so we are unable to imagine different, possible lives. These writers’ works suggest a hidden richness that has been poorly acknowledged, and a courageousness to break with those old expectations.

It’s the honest stories—the ones that speak to our country’s messy, unjust history and the calamities in their aftermath—that have long been missing from the conversation. These Malaysian women writers are changing the game by insisting on the value of their stories and perspectives:

Though I Get Home by YZ Chin

The loosely connected stories orbit around Isabella Sin, an inadvertent prisoner of conscience in Kamunting Detention Centre. Kamunting became notorious for its role in Operation Lalang crackdown in the ’80s, which ended with the government’s current stranglehold on the press. While Though I Get Home doesn’t directly reference this political history (likely no coincidence that Isabella is nicknamed “Isa”, the shorthand for Internal Security Act), its influences are obvious: characters are constantly dissembling, and the danger of exposure shadows every step. There is the hovering sense of a world on the cusp of transformation, as small-town Taiping reluctantly gives way to shiny, plastic Kuala Lumpur. Through the stories’ fragmentary, circular quality, Chin dives into the murky margins where the personal meets the political—hints and secrets abound, scattered like breadcrumbs leading to some unknowable past that no one wants to give voice to.

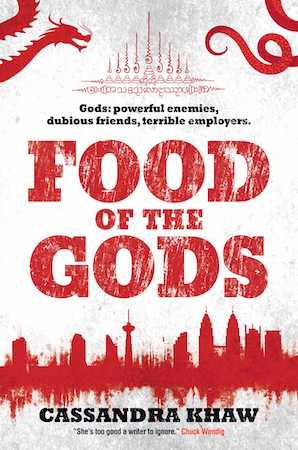

Food of the Gods by Cassandra Khaw

Rupert Wong—a cannibal chef with a knack for turning unsuspecting tourists into food—has been enlisted to investigate the brutal murder of a dragon’s daughter in exchange for his vampiric girlfriend’s freedom. The first in a series about the Seneschal of Kuala Lumpur, Khaw deftly conjures a plot out of bureaucratic deadlock—what’s more Malaysian than that?—and riffs on cross-cultural mythologies. From beginning to end, the novel is steeped in the gory, fetid underworld of gods, bad spirits, and even worse bargains, its prose sliding easily between languages and space. The Kuala Lumpur of this novel isn’t neatly subdivided between the living and the not-quite human; it is a city rife with supernatural and manmade chaos.

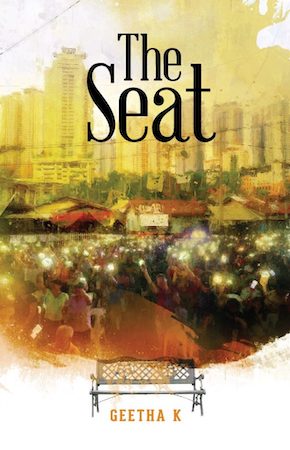

The Seat by Geetha K.

The 14th General Election, to put it mildly, changed the trajectory of Malaysian history and rewrote what is possible in our politics. While the events of 2018 have more or less passed into the realm of myth, The Seat offers an opportunity for readers to re-immerse themselves in those heady days by blending memoir and story into a kind of “verbatim” fiction. The fight for Segambut—a parliamentary constituency in Kuala Lumpur—really happened and the speeches by political characters can be accessed online. A clarity of place grounds the novel: Geetha devotes long stretches of prose to descriptions of the geographies and textures of Satya’s life in vivid detail, charting where the old where meets the new, speaking to each across time.

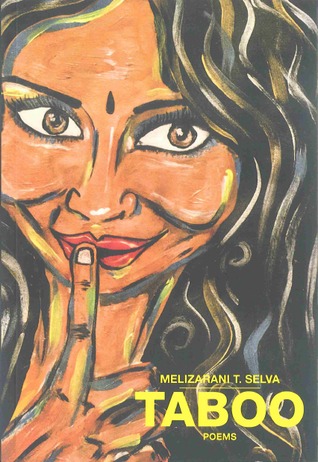

Taboo by Melizarani T. Selva

Spoken word performance has had an inordinate influence on the most recent generation of Malaysian poets, thanks in part to the form’s physicality, which allows poets to navigate communication in a country where most people are at least bilingual. Taboo, Melizarani’s first collection, probes the liminal space between the physical and linguistic, asking what life is possible (or permissible) in a place that can be suffocatingly restrictive for someone who is both Indian and female. Rejecting any neat conclusions about the incongruity of taboos with the modern era, Melizarani picks fights with tyrants and bad politics in language that is physical but playful, probing and self-possessed. Her narrators are always speaking with their mouths open, tongues wagging in defiance.

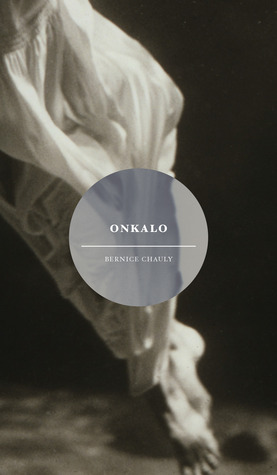

Onkalo by Bernice Chauly

Chauly’s entire body of work is obsessed with locating individual meaning amid senseless decay and corruption. Onkalo (Finnish for “small cave” or “cavity”) is a slim volume full of chthonic and restless energy that first accuses, then whispers. The first poem, “Jerit” (Malay for “howl”) opens with a scream of barely-leashed anger at Malaysia’s many injustices, a thread that recurs throughout the collection. At times, the poems slide into a haunted quest for the “right to write,” that parallels (and, at times, is dissolved by) the narrators’ longing for a lover’s constancy. However she may search, though, the writer retains supremacy:

“I deserve this

I deserve to be known again

no longer a lost continent

no longer lost.”

The Girl and the Ghost by Hanna Alkaf

Malay Muslim women novelists writing in English are a rare breed, and rarer still are Malay Muslim women characters whose narratives aren’t driven in some part by their identities as Muslims or as women. The Girl and the Ghost’s main character, Suraya, is a revelation armed with a rich interior life that Hanna marshals to explore ideas around the hard work required to connect across gaps of time, distance, and feeling. Throughout the novel, Suraya navigates an unlikely friendship seeded and shaped by loss with Pink, a ghostly inheritance from her grandmother. Narratives about women trying to reconnect with absent mothers of all kinds are the locus of Hanna’s work, as are her depictions of a heat-swamped Malaysia—a distinct setting that is both familiar and strange.

Lake Like a Mirror by Ho Sok Fong, translated from Chinese by Natascha Bruce

In Ho’s award-winning short stories, feminine interiority offers an escape from a life stifled by male chauvinism—right up until the moment it can’t. Then we get revenge, bloodthirsty pontianaks, and stepmother-shaped puzzle pieces. With a specificity that belies their familiarity, Ho maps a vision of Malaysia’s sleepy small towns characterised by absence and presence: the wilderness at the margins, and those lost to them; the old people who decay in place, and the young gone to big cities. Here, nothing and everything seems to change: a young girl gets stuck in a time loop between her lovelorn aunt and a mysterious visitor, while an old woman loses herself in loneliness amidst a cluttered sundry shop. She writes:

“Sometimes, people carried on living even after a part of them had died. Then that dead part started to reincarnate.”

Spirits Abroad by Zen Cho

Zen Cho is perhaps best known abroad for her Hugo Award-winning Regency fantasies, but her 2014 collection—first published by local house Fixi Novo, and soon to be reissued by Small Beer Press—is a criminally-underrated gem that weaves paranormal interruption into mundane Malaysian life. The collection offers a kaleidoscopic vision of a society living cheek-by-jowl with a community of ghosts, spirits, and mythical creatures, in a state of not-quite harmony. At turns unfazed by their presence and annoyed by their mischief, Cho’s characters move through the world with an enviable understanding of their place within it. In the logic of the Spirits Abroad extended universe, “magic” isn’t a force to be wielded or feared—it is air itself, as powerful and common as dirt.

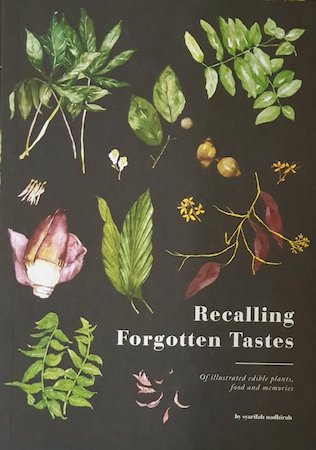

Recalling Forgotten Tastes: Of Illustrated Edible Plants, Food and Memories by Syarifah Nadhirah

Part botanical record, part sociological census, part oral history, and part memoir, Recalling Forgotten Tastes seeks to center the environmental and culinary knowledge of Peninsular Malaysia’s indigenous Orang Asli communities, specifically the Semai and Temuan peoples. Far more than just a compendium of plants and their uses, Syarifah’s delicate illustrations are accompanied by accounts of each community’s displacement, how they have been continually robbed of their land. In doing so, she has inadvertently created a new geographical history of where the Orang Asli live, and how, in spite of it all, they remain startlingly resistant in the face of widespread deforestation and loss.

The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya: Volume I by Reimena Yee

Zeynel—the titular carpet merchant of this Eisner-nominated work—is a man of faith left unmoored from life and love thanks to a chance encounter with a vampiric djinni. Inspired by Gothic romances, vampire fiction, and Victorian detective stories, The Carpet Merchant duology is rendered in a rich visual language inspired by Turkish motifs and techniques that spill across the page and beyond the border. Yee’s painstaking research, intricately woven into the plot’s treatment of Turkish artwork and the Islamic faith, makes a subtle argument that it is possible to depict cultures that are not your own with sensitivity—but only if you’re willing to put in the work.

The post 10 Books by Malaysian Women Writers You Should be Reading appeared first on Electric Literature.

Source : 10 Books by Malaysian Women Writers You Should be Reading