Glory Edim, founder of Well-Read Black Girl, on her new anthology celebrating Black women in literature

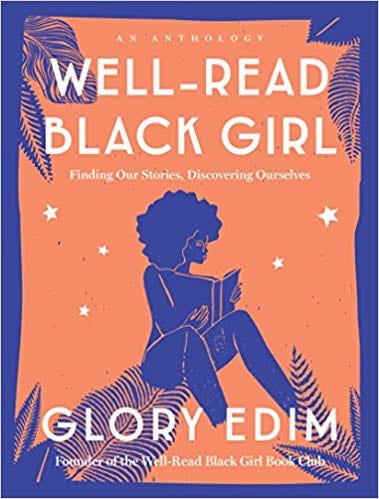

Since its inception in 2015, Well-Read Black Girl (WRBG) has become one of the most influential and nourishing spaces for Black female bibliophiles. Founder Glory Edim has been steadfast and consistent in not only her love of books but especially and prominently books by Black women. It seemed a natural course of events that an essay anthology Well-Read Black Girl: Finding Our Stories, Discovering Ourselves would follow, and thanks to Ballantine Books, it has.

One of Edim’s most identifying characteristics is her affection for both people and books, showcased in the enthusiasm she exudes in person and online. Her passion for discussing all things literary, Black, and female has made her a respected (and necessary) book influencer — she was awarded the LA Times Innovator of the Year award this year — as well as an active literary cheerleader. She celebrates literature and Black woman artists not only with her monthly book club, but through her growing social media accounts and the Well-Read Black Girl Festival (the second annual festival will take place on November 10th in Brooklyn). Through these endeavors Edim has carved a rightful place as an essential voice within our industry. The Well-Read Black Girl anthology serves as the next stepping stone, and then there’s a memoir we all have to look forward to.

Edim and I spoke, editor to editor, about the empathetic nature of Black women as people and readers, her keen eye in curating her anthology to showcase a bevy of voices we do and should know, and her dedicated vision that’s allowed her to learn more about what she wants to see in the industry as well as what she aims to bring to it.

Jennifer Baker: What’s interesting [about the Well-Read Black Girl anthology] is that you approach people and you give them a kind of topic or thesis statement, but you don’t know what you’re getting. This felt like it really worked out in a very keen way and everyone is so specific in what they were saying. It’s not to say that there isn’t overlap or there isn’t a throughline, but it never felt repetitive. Because these are individual pieces that threatens to happen in an anthology.

Glory Edim: I was really nervous that everyone simply would talk about Toni Morrison.

Jennifer: She is the Canon basically.

Glory: She is. And nothing would be wrong with that. But I was worried every essay would be a tribute to Toni Morrison [which] would be a whole different book. I was afraid there’d be a repetitive nature in the tone of it. But that didn’t happen at all. And I think that was because I was very particular about curating the nature of the selection of voices. Most people I had met one-on-one through the book club, everyone from Zinzi Clemmons to Jesmyn Ward. There were two that were cold calls. I didn’t have a relationship with Lynn Nottage prior to this. We follow each other on Twitter and I was constantly loving everything she does. And that’s another thing about the publishing world doesn’t know that I keep to myself, but I’m a huge theatre nerd and that’s kind of my escape, so I’m obsessed with Lynn Nottage. So when she said yes that was such a highlight.

Even Barbara Smith. Similar to Lynn, I did not have a relationship with her. She is the sweetest. I wanted to have her because she essentially is the pinnacle of Black feminist queer theory and her publishing company, Kitchen Table (Women of Color Press), has so many Black women. She being an elder and her experience as an activist is so vital. In her essay she talks about James Baldwin. I just kind of assumed everyone would naturally talk about a Black woman. When she wrote about Baldwin it was so perfect, it makes so much sense. People just really came at it from their own personal experiences.

‘Black Liberation Means the Freedom to Figure Things Out For Ourselves’

Jennifer: Barbara Smith comments on biography and not necessarily searching for the same themes as she would fiction. Lincoln is white, but maybe there are aspects of Lincoln that I can relate to even in his whiteness/his maleness/his elite space. In terms of class and problems and things like that we’re constantly negotiating or recognizing the quality in other people’s work and that’s how I feel as a Black woman and an avid reader. In your anthology it’s not necessarily qualifying but providing that space for recognizing “this is the value for us of our stories.” Do you feel like that’s a conversation we’re constantly forced to have as Black women?

Glory: At the end of the day this book is literally of Black women across the Diaspora that are all seeking meaning and identity. In every work of fiction or every memoir, the core of it is about identity, meaning people are seeking meaning in so many different aspects of their lives. And thankfully there are books you can look at for help, but there’s still that void. And I agree with you, we have the ability to see ourselves in other people. Black women are the most empathetic group of people in the book because we can empathize. That is why the Black Lives Matter hashtag is so powerful and [the] three women who run it are Black, feminist, queer women. So, how much more can you understand identity with those three levels there? The goal is to have people have an understanding of their own identity and their own livelihood, but also reach out and find nourishment in others too, and be able to have parallel stories and exchange ideas, and really find ways to validate one another. I believe as Black women we have given that generosity to so many other people that I would just like it to be reciprocated. There is no reason a person should pick up a book by Jacqueline Woodson and not understand it and not see themselves. The stories lifelines are there, you do not need to be a Black woman to understand what Jacqueline Woodson is saying to the world. I read Little Women. I read Moby Dick. And I saw myself, not in a (literal) seeing myself, but I was able to understand and empathize with it and the importance it. That means that analysis and that generosity in reading should be given to Black women and our stories across the canon, whether it’s Phillis Wheatley or Jacqueline Woodson.

In every work of fiction or every memoir, the core of it is about identity, meaning people are seeking meaning in so many different aspects of their lives.

Jennifer: Getting into the heart of that, what came up was the mirrors and windows — the reflection of self versus looking inside. Which books kind of keyed into us that kind of visibility. And it turned out to be a lot about honesty or the pursuit of honesty. When I was talking to Kiese [Laymon] about his book, he made a good point I think we’re all trying to pursue a form of honesty. So when you were editing this did you see that coming together of “Oh, this honesty is in our stories”?

Glory: That is literally at the essence of what I was trying to capture, all the levels of transparency and vulnerability. Because when you come through the WRBG book club that is what happens. When you’re sitting next to each other and sharing ideas and you’re talking about the protagonist of this book but you’re also talking about your personal experiences and it’s all mashed up together in this one beautiful — I don’t even know how to explain it.

When you’re in these spaces and you’re building them with intentionality and you add a spirit to them, you’re very keen about how you want others to feel. So I’m very concerned about the feel of the room and how people are welcomed in and having a positive, affirming experience. That is what I wanted the anthology to be: a positive, affirming reading experience that simulates what we do in the WRBG book club. By the time you read every book you’re confronted with so many questions and emotions. I wanted the reader to close the book feeling satisfied that they saw a reflection of themselves on the pages. But that they also will be curious to dig deeper and ask questions and look at the facts and the analysis of all these beautiful contributors. Like look beyond just what we see. Like you said, we said about the essays “look beyond the mirror into the substance of the person and the language and the literature of Black women.” I think that’s what everyone, myself as the editor and this beautiful collection of contributors, portrayed.

Is It Possible to Write a Truthful Memoir?

Jennifer: And speaking as a community it is and isn’t an insular project. It really speaks to the Black female community or female-identifying (I don’t want to exclude the nonbinary community).

Glory: Yes, you’re right.

Jennifer: So I’m thinking about those other reads. You didn’t create this for white people. That’s not the reason for its existence. But the presumption, especially by publishers in this industry, is that they will read it.

Glory: I have not been concerned about that, even though — and this is the part where I am very grateful that I do not feel completely in the publishing industry, because I don’t think that way. I understand that that matters to people, but I’m really proud that my work has been created exclusively for Black women, and the community ventures for ourselves. The book is a reflection of that. The book club is a reflection of that. The festival is that same energy. I’m also so thankful that my experience at an HBCU has prepared me for this because so many things that I’m working towards I am not thinking about the white gaze. I am not thinking about how others will respond to it. I’m simply thinking about what is the best I can do for my community? And that has been so affirming, but also it gives me so much room to be innovative and not be tethered to stereotypes or ideas of what we should be.

Not everyone has the idea that of course Blackness should be at the forefront or a priority, because I’m Black and I’m a woman. And of course not to keep it binary, that is my perspective and I hold true to it and the one I always wanna make a priority with someone on the questions on development in my personal relationships, Black women are always the number one thing that I’m focused on. And I think that’s okay and I think more Black women need to move in that space and be less fearful of assimilating or trying to make white folks happy. I think we need to move away from that kind of thinking. Which is hard, it’s just hard especially when you’re in spaces that are predominantly white. But walking in our power and knowing our truth is what needs to happen to make radical change. It’s just a little something I’m confronted with and I’m working towards. There’s like two imprints that I adore and support constantly. 37 INK, I love Dawn Davis. I love Chris Jackson from One World. But after that how many imprints can you really say where the community is fully acknowledged? I’d love an opportunity to have my own imprint. Someone give me funding for that. I’d love to publish books. There’s more work that needs to be changed not only on the writer/reader side but within the hierarchy of publishing itself.

I think more Black women need to move in that space and be less fearful of assimilating or trying to make white folks happy.

Jennifer: Also you’re helping give Black women’s work a larger platform, because the issue has always been the platform. It’s never been the non-existence. It’s been the visibility.

Glory: Right, it’s the visibility. I think of Mary Helen Washington who is still alive but she is fucking amazing and she edited the book Black-Eyed Susans and Midnight Birds and it’s all about fiction writers, stories by and about Black women. So it’s all female writers, passages from Toni Morrison to all the literary greats in one book. And she’s a phenomenal literary scholar and I’m like, “Where is our love Mary Helen Washington who really set the precedent for all these things?” It’s not only the five writers we can constantly name who we love: Maya, Alice, Toni. But looking at Mary Helen Washington’s work, talking more about Paule Marshall really looking at the literary scholars of the work too is so important. When we’re talking about the intensive study of certain literary classics it should not stop at Walt Whitman and Theroux, we have to have more stories by Black women included in the canon.

This Anthology Is the Black Women’s Book Club You Always Wanted was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : This Anthology Is the Black Women’s Book Club You Always Wanted