Climate 101 is a Mashable series that answers provoking and salient questions about Earth’s warming climate.

The last time CO2 levels were as high as today, ocean waters drowned the lands where metropolises like Houston, Miami, and New York City now exist.

It’s a time called the Pliocene or mid-Pliocene, some 3 million years ago, when sea levels were around 30 feet higher (but possibly much more) and giant camels dwelled in a forested high Arctic. The Pliocene was a significantly warmer world, likely at some 5 degrees Fahrenheit (around 3 degrees Celsius) warmer than pre-Industrial temperatures of the late 1800s. Much of the Arctic, which today is largely clad in ice, had melted. Heat-trapping carbon dioxide levels, a major temperature lever, hovered around 400 parts per million, or ppm. Today, these levels are similar but relentlessly rising, at over 420 ppm.

Humanity is currently on track to warm Earth to Pliocene-like temperatures by century’s end — unless nations ambitiously slash carbon emissions in the coming decades. Sea levels, of course, won’t instantly rise by tens of feet: Miles-thick ice sheets take many centuries to thousands of years to melt. But, critically, humanity is already setting the stage for a relatively quick return to Pliocene climes, or climes at least significantly warmer than now. It’s happening fast. When CO2 naturally increases in the atmosphere, pockets of ancient air preserved in ice show this CO2 rise happens gradually, over thousands of years. But today, carbon dioxide levels are skyrocketing as humans burn long-buried fossil fuels.

“CO2 in the atmosphere has gone up 100 ppm in my lifetime,” said Kathleen Benison, a geologist at West Virginia University who researches past climates. “That’s incredibly fast geologically.”

The first images of Earth are chilling

“You don’t have to be a scientist to realize something totally weird is going on, and that weird thing is humans,” noted Dan Lunt, a climate scientist at the University of Bristol who has researched the Pliocene.

Update April 18, 2023: Since this article was originally published in 2021, atmospheric CO2 levels have continued to rise. Scientists recorded the first reading of CO2 breaching 423 ppm on April 16. Overall, in 2022, CO2 concentrations averaged out to 417.2 ppm, which is “more than 50 percent above pre-industrial levels,” according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

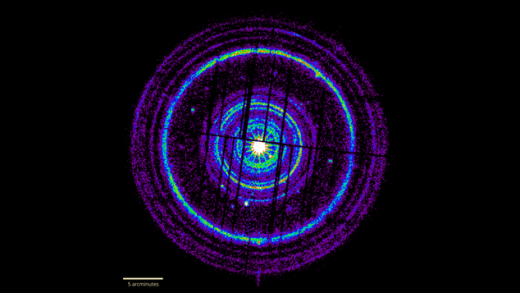

Credit: NASA

The problematic Pliocene

Sure, it takes a long time for sea levels to catch up with Earth’s warming. But in a plethora of other ways, the planet is already reacting to about 2 F (1.1 C) of warming since the late 1800s: Wildfires are surging in the U.S., major Antarctic ice sheets have destabilized, heat waves are smashing records, storms are intensifying, and beyond.

More warming will further exacerbate these consequences of increased heat. It will get worse. But will it get Pliocene bad? That’s up to the most fickle, unpredictable factor of the climate equation: humans.

“CO2 levels are going to increase,” said Lunt. “We could hit the Pliocene in terms of temperature. But it depends on how rapidly we emit [greenhouse gases].”

“CO2 levels are going to increase.”

Some of the human-driven changes happening on Earth today won’t be reversed for centuries or thousands of years. In large part, that’s because civilization continues to deposit prodigious loads of carbon into the atmosphere each year, and all these heat-trapping gases won’t magically vanish from the air, even if we instantly stop adding carbon to the atmosphere. Rather, they’ll have impacts upon the planet — like gradually rising seas and acidifying oceans — for at least centuries. Already, sea levels have risen by some eight to nine inches since the late 1800s, and a conservative estimate, from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, is sea levels will rise by another one to two feet by the century’s end. But, this could very well be more like two or three feet, or even more depending on what Antarctica’s colossal, melting Thwaites Glacier (it’s the size of Britain) purges into the sea this century.

“Sea level rise and ocean acidification are permanent on a human time scale,” said Julie Brigham-Grette, a geologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst who researches how the Arctic has changed since the Pliocene.

Credit: NASA

The Pliocene certainly can’t give us all the answers for where we’re headed. We don’t know, for example, how quickly the seas rose during this far-off period. But the Pliocene does show us how sensitive parts of Earth are to just a few degrees of warming. For instance, much of the vast Greenland ice sheet, which is two and a half times the size of Texas, melted during the warmer Pliocene. And ancient evidence of long-ago beaches, dated to the Pliocene, show where past shorelines lay: A ballpark height of 30 feet or so higher than today is ominous.

“That means the ice sheets are really sensitive to a modest amount of warming,” said Rob DeConto, a professor of climatology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst who studies the response of ice sheets to a warming climate.

This doesn’t bode well for human civilization, which heavily populates the coastlines. “That’s where civilization has built much of its infrastructure,” said DeConto. “We’re a species that gravitated toward the coast.”

Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable’s Top Stories newsletter today.

Pliocene warmth

Earth’s CO2 levels have always naturally wavered. Humans didn’t exist (and wouldn’t exist for millions of years) during the Pliocene — though our hirsute primate ancestors were already walking around Africa at the time.

So what explains the high Pliocene CO2 levels (400 ppm) without a world of fuel-guzzling cars and coal-fired power plants? The answer lies in deep time.

Long before the Pliocene, CO2 levels were extremely elevated during the age of the dinosaurs (which ended 65 million years ago), perhaps at some 2,000 to 4,000 ppm. Tremendous CO2 emissions, from incessant and extreme volcanism, heated Earth and allowed dinosaurs to roam a sultry Antarctic. But over millions of years, Earth’s natural processes (specifically the slow, grinding, but potent process of rocks absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere, dubbed “the rock thermostat”) gradually reduced CO2 levels to some 400 ppm during the Pliocene. (We know this because there are indirect, though reliable, ways to gauge Earth’s CO2 levels from millions of years ago, including the chemical make-up of long-dead plankton and the evidence stored in the breathing cells, or stomata, of ancient plants.)

“We’re on our way to the Pliocene.”

After the Pliocene, Earth continued to pull CO2 from the air, finally settling CO2 levels between some 200 to 280 ppm during the more recent ice ages, when mammoths, mastodons, and giant sloths dominated a cooler Earth, and humans eventually appeared. But humanity, by rapidly digging up and burning fossil fuels, has now promptly returned CO2 to Pliocene levels.

“We, in 150 years, have completely reversed everything the ‘rock thermostat’ has done in the last 3 million years,” explained Brigham-Grette. “The transition from a warm Arctic to a cold one that has ice sheets took a million years. We’re jumping out of that in less than 150 years.”

Tweet may have been deleted

(opens in a new tab)

Indeed, the Arctic has changed dramatically in just the last 40 years. Arctic sea ice is in rapid decline. Greenland’s melting is off the charts.

Humanity, fortunately, still has the ability to stabilize Earth’s temperatures this century at levels that would avoid catastrophic impacts like more extreme storms, coral devastation, punishing heat, and beyond. But, as of now, we’re on a trajectory to the climes of 3 million years ago. (And in some respects — notably atmospheric CO2 — we’re already there.)

“We’re on our way to the Pliocene,” said Brigham-Grette.

This story was originally published in April 2021 and has been updated with more information about the drastic CO2 increase in Earth’s atmosphere.

Source : What Earth was like last time CO2 levels were so crazily high