My first book, Ancestor Trouble, came out this year, and I remain as engaged with the concerns that preoccupied me while writing it as I was before it was published. All my life I’ve been drawn to stories and ponderings on the corrosive effects of family secrets, about recurring tendencies, wounds, and harms in individual families, and the reverberations of all this in the larger world. I wrote about these questions on my blog back in the aughts, sometimes in personal posts but also in broader ones about books and art and politics. So I’m encouraged by our national preoccupation with ideas of intergenerational trauma. I hope we’ll increasingly recognize the ways that those ideas so naturally complement our closer attention to the history of oppressive cultural systems (and the complicity of some of our ancestors in their construction). I’m also energized by deepening understandings of kinship that include our beyond-human relations, that extend to the earth itself and are informed by spiritual traditions and practices that endured despite the individualistic emphasis of Anglo-European modernity. At the same time, I sense an emerging critical frustration around stories that excavate these questions. (Parul Seghal‘s “The Case Against the Trauma Plot” comes to mind.) And sure, there will always be facile variations of any kind of story, any form of investigation. But I’d argue that these questions are valuable and eternal and that their suppression through the Enlightenment’s centering of the individual has been both toxic for the world at large and a tragedy for humanity.

I read too many good books to list in full here, so I’ll focus on the ones I love that, to me at least, touch on these themes in some way. The first two are out in April of next year, but you can preorder them now as gifts to yourself. Dionne Ford‘s tenacious, openhearted, and often poetic Go Back and Get It: A Memoir of Race, Inheritance, and Intergenerational Healing took my breath away. On her thirty-eighth birthday, Ford found a photo of her great-great grandmother with the white man who’d enslaved her—also Ford’s ancestor—and two of the six children they had together. Seeing these forerunners of her own most wrenching experiences deepened and clarified a search that Ford had been moving toward since childhood. The result is transcendent: memoir and quest, critique and exhortation, a distillation of wisdom profound as the Psalms. And in Mott Street: A Chinese American Family’s Story of Exclusion and Homecoming, Ava Chin blazes a path through the fictions made necessary by the Chinese Exclusion Act to a gorgeously intimate story of her own family across generations and a powerful indictment of the ways this country’s past xenophobia reverberates in the present. She discovers that many of her ancestors’ histories flow through a single building on Mott Street, a place that simultaneously grounds and unleashes the spirit of their collective story. It’s a beautiful and necessary book.

I read too many good books to list in full here, so I’ll focus on the ones I love that, to me at least, touch on these themes in some way. The first two are out in April of next year, but you can preorder them now as gifts to yourself. Dionne Ford‘s tenacious, openhearted, and often poetic Go Back and Get It: A Memoir of Race, Inheritance, and Intergenerational Healing took my breath away. On her thirty-eighth birthday, Ford found a photo of her great-great grandmother with the white man who’d enslaved her—also Ford’s ancestor—and two of the six children they had together. Seeing these forerunners of her own most wrenching experiences deepened and clarified a search that Ford had been moving toward since childhood. The result is transcendent: memoir and quest, critique and exhortation, a distillation of wisdom profound as the Psalms. And in Mott Street: A Chinese American Family’s Story of Exclusion and Homecoming, Ava Chin blazes a path through the fictions made necessary by the Chinese Exclusion Act to a gorgeously intimate story of her own family across generations and a powerful indictment of the ways this country’s past xenophobia reverberates in the present. She discovers that many of her ancestors’ histories flow through a single building on Mott Street, a place that simultaneously grounds and unleashes the spirit of their collective story. It’s a beautiful and necessary book.

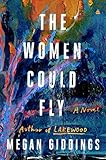

As for 2022 novels, I adored Xochitl Gonzalez‘s Olga Dies Dreaming, a book that opens with a wedding planner scheming about fancy napkins and has the pleasures of a fast-paced confection while also going deep into and being brilliant on complex questions about absent moms, the Puerto Rican diaspora, gentrifying Brooklyn, and bad decisions in love. It’s the kind of story I wish I could read again for the first time. The same is true for Alice Elliott Dark‘s Fellowship Point, about an elderly writer who’s secretly published widely-acclaimed novels borrowed from her friends’ lives under a pseudonym for decades and is facing writer’s block. The book has immense tenacity of spirit, an incredible ability to go deep with each of its characters—including a particular place on the earth—and also a gorgeous gentleness. Megan Giddings‘s The Women Could Fly, my most recent read, is another book I couldn’t put down. It’s set in a world where nature is suspect, historical witches are reviled and festishized, girls and women are constantly monitored for signs of witchcraft and are expected to marry men by the age of thirty or see their rights severely curtailed. Whether magic exists is a recurring question. Low-key questions of inheritance bubble up more overtly as the book goes on. Ann Leary‘s The Foundling is a page-turner that’s deeply preoccupied with the history of eugenics in this country and its intersection with institutions where women were locked up for all kinds of reasons. Leary’s grandmother was raised in an orphanage and later went on to work in the institution that became the basis for the novel. I also devoured Dani Shapiro‘s luminous and connective Signal Fires, which is concerned with so many of the questions Shapiro mines best and that are also alive for me, in particular family secrets, and the hidden threads that unite us all. In older books, Lauren Groff‘s Matrix blew my mind last year and ultimately sent me deep into her backlist, whereupon I discovered the glorious Arcadia. Fellow Madeline Miller fans who haven’t seen the news might like to know that she has a haunting new short story out as a bound book: Galatea. It’s impossible for me to separate the resonance of Emma Straub‘s tender latest, This Time Tomorrow, from the real life death of her father, Peter Straub, also a beloved writer.

As for 2022 novels, I adored Xochitl Gonzalez‘s Olga Dies Dreaming, a book that opens with a wedding planner scheming about fancy napkins and has the pleasures of a fast-paced confection while also going deep into and being brilliant on complex questions about absent moms, the Puerto Rican diaspora, gentrifying Brooklyn, and bad decisions in love. It’s the kind of story I wish I could read again for the first time. The same is true for Alice Elliott Dark‘s Fellowship Point, about an elderly writer who’s secretly published widely-acclaimed novels borrowed from her friends’ lives under a pseudonym for decades and is facing writer’s block. The book has immense tenacity of spirit, an incredible ability to go deep with each of its characters—including a particular place on the earth—and also a gorgeous gentleness. Megan Giddings‘s The Women Could Fly, my most recent read, is another book I couldn’t put down. It’s set in a world where nature is suspect, historical witches are reviled and festishized, girls and women are constantly monitored for signs of witchcraft and are expected to marry men by the age of thirty or see their rights severely curtailed. Whether magic exists is a recurring question. Low-key questions of inheritance bubble up more overtly as the book goes on. Ann Leary‘s The Foundling is a page-turner that’s deeply preoccupied with the history of eugenics in this country and its intersection with institutions where women were locked up for all kinds of reasons. Leary’s grandmother was raised in an orphanage and later went on to work in the institution that became the basis for the novel. I also devoured Dani Shapiro‘s luminous and connective Signal Fires, which is concerned with so many of the questions Shapiro mines best and that are also alive for me, in particular family secrets, and the hidden threads that unite us all. In older books, Lauren Groff‘s Matrix blew my mind last year and ultimately sent me deep into her backlist, whereupon I discovered the glorious Arcadia. Fellow Madeline Miller fans who haven’t seen the news might like to know that she has a haunting new short story out as a bound book: Galatea. It’s impossible for me to separate the resonance of Emma Straub‘s tender latest, This Time Tomorrow, from the real life death of her father, Peter Straub, also a beloved writer.

In 2022 nonfiction, Heretic, by my friend and fellow ex-evangelical Jeanna Kadlec, is an outstanding debut memoir, clear, elegant, and precise as etched glass. Kadlec recounts a detachment from herself so profound and carefully inculcated that desire for anyone other than God felt like transgression. Her prose is wise and erudite, undergirded by plain speech and an open heart. The book is a light unto the path of every former evangelical who longs for communion beyond the condemnation and spiritual abuse of the church, and a crucial window for outsiders into what it’s like to grow up handed a birthright of original sin. Ada Calhoun‘s Also A Poet: Frank O’Hara, My Father, and Me deserves every bit of the praise it’s garnered, as do Ed Yong‘s An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us and Imani Perry‘s South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon Line to Understand the Soul of America. I was thrilled to see Tanaïs‘s In Sensorium: Notes for My People be awarded the Kirkus Prize for Nonfiction. Dan Bouk‘s Democracy’s Data: The Hidden Stories in the U.S. Census and How to Read Them is smart fun for genealogy nerds but also a must-read for anyone interested in the construction and systemic effects of big data. Taylor Harris‘s This Boy We Made: A Memoir of Motherhood, Genetics, and Facing the Unknown and Hafizah Augustus Geter‘s The Black Period: On Personhood Race, and Origin deserve more attention than they’ve gotten. Stephanie Foo‘s What My Bones Know: A Memoir of Healing From Complex Trauma is a book I recommend widely to people who grew up in abusive situations and are struggling to find a way forward. All year I’ve been making my way through Kinship: Belonging in a World of Relations, a wonderful and mighty wide-ranging five-volume set on interconnectedness between humans and our broader “planetary tangle of relations,” edited by Gavin Van Horn, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and John Hausdoerffer. It was published in 2021. And I’m just starting into Eleanor Parker‘s Winters in the World: A Journey Through the Anglo-Saxon Year, which is great so far.

In 2022 nonfiction, Heretic, by my friend and fellow ex-evangelical Jeanna Kadlec, is an outstanding debut memoir, clear, elegant, and precise as etched glass. Kadlec recounts a detachment from herself so profound and carefully inculcated that desire for anyone other than God felt like transgression. Her prose is wise and erudite, undergirded by plain speech and an open heart. The book is a light unto the path of every former evangelical who longs for communion beyond the condemnation and spiritual abuse of the church, and a crucial window for outsiders into what it’s like to grow up handed a birthright of original sin. Ada Calhoun‘s Also A Poet: Frank O’Hara, My Father, and Me deserves every bit of the praise it’s garnered, as do Ed Yong‘s An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us and Imani Perry‘s South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon Line to Understand the Soul of America. I was thrilled to see Tanaïs‘s In Sensorium: Notes for My People be awarded the Kirkus Prize for Nonfiction. Dan Bouk‘s Democracy’s Data: The Hidden Stories in the U.S. Census and How to Read Them is smart fun for genealogy nerds but also a must-read for anyone interested in the construction and systemic effects of big data. Taylor Harris‘s This Boy We Made: A Memoir of Motherhood, Genetics, and Facing the Unknown and Hafizah Augustus Geter‘s The Black Period: On Personhood Race, and Origin deserve more attention than they’ve gotten. Stephanie Foo‘s What My Bones Know: A Memoir of Healing From Complex Trauma is a book I recommend widely to people who grew up in abusive situations and are struggling to find a way forward. All year I’ve been making my way through Kinship: Belonging in a World of Relations, a wonderful and mighty wide-ranging five-volume set on interconnectedness between humans and our broader “planetary tangle of relations,” edited by Gavin Van Horn, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and John Hausdoerffer. It was published in 2021. And I’m just starting into Eleanor Parker‘s Winters in the World: A Journey Through the Anglo-Saxon Year, which is great so far.

The post A Year in Reading: Maud Newton appeared first on The Millions.

Source : A Year in Reading: Maud Newton