I only speak one language: English. Knowing English is a privilege, both in life and in the world of books. It’s one I’m aware of and grateful for. Perhaps it’s because of that that I love finding untranslated words from other languages in books written in English. It’s a beautiful reminder that the world is so much bigger than one language.

I love translated literature. But even the best translations leave something behind. So much of language is steeped in the culture and history of a place. Some things can’t be translated — not exactly, not truly. This isn’t good or bad. It’s just the way language works. When I come across words in a language I don’t speak in a book I’m reading, it’s a little reminder of that expansiveness. It feels, to me, like another sort of gift. The world will always be bigger than my understanding of it. I don’t have to understand every part of a book to love it. Some parts of a story aren’t meant for me, and that’s okay.

There’s a wonderful duality that arises when authors choose to leave untranslated words in their books. It makes space for books to be different things to different readers. None of the untranslated language in any of these books stopped me from loving them. The unfamiliar words didn’t take me out of the story. But readers who do speak those languages, who do come from those cultures, will surely have different a reading experience. They’ll get to see pieces of the story I can’t see.

America Is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo is a story set in a primarily Filipine community in California, and it contains a lot of untranslated Tagalog and Ilocano. It’s one of my favorite novels. Google is a thing that exists; when I first read it, I could have typed all those phrases into my computer to find out what they meant. What I did instead was read up on the languages of the Philippines. The fact that Castillo left so many words untranslated wasn’t a barrier to my understanding. It was an invitation for me, a white American reader, to be curious and thoughtful, to put time and work into learning something new. Likewise, her choice to leave those Tagalog words untranslated takes the burden off native speakers. While reading a novel about characters who speak Tagalog, why should readers who also speak Tagalog have to wade through explanations simply for the ease of English-speaking readers?

Leaving certain words untranslated is often a way to decenter whiteness. It’s an acknowledgement that not everything is translatable, that some parts of a culture or a language will always remain unknown to those who live outside of it. It’s a gentle and loving reminder that this is, in fact, okay. I can love a book about people who are different from me without understanding every nuance of those characters, while sometime else experiences the specific joy of seeing their language and culture reflected in those characters.

These eight books, all written in English, contain untranslated words from other languages. They are celebrate and honor that duality.

America is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo (Tagalog, Ilocano)

This beautiful family epic follows Hero, a Filipina immigrant who arrives in California to live with her aunt and uncle after spending most of her 20s as part of the resistance movement in the Philippines. It’s a complex book about healing from trauma, blood and chosen family, queer love, and a whole lot more.

Fiebre Tropical by Julian Delgado Lopera (Spanish)

The first sentence of this electric, sometimes dizzying novel, bursts with Spanish words, a pattern that continues for the rest of the book. At 15, Francisca arrives in Miami from Bogota, and soon finds herself swept into the world of her mother’s evangelical church. Her brash, loving, funny, and absolutely unapologetic voice shines through as she discovers her queerness, falls in love for the first time, and struggles through a series of family crisis.

Things We Lost to the Water by Eric Nguyen (Vietnamese)

This haunting, gorgeously written novel begins with Huong arriving in New Orleans with her two young sons, devastated that her husband has remained behind in Vietnam. Over the next decades, she slowly builds a life for herself and her family in a new city. Moving between POVs, this book explores the long shadows of war, exile, grief, and longing. As the boys grow up and into themselves, the whole family begins to reckon with what it means to call somewhere home, and what it means to belong to a family, culture, or country.

Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray by Anita Heiss (Wiradjuri)

This historical novel opens in Gundagai, Australia, in 1852. Wagadhaany, a member of the Wiradjuri Nation, lives with her family near the massive Murrumbidgee River. When a flood destroys the white settlement, she’s forced to go with the family who employs her to their new home in a different part of the country. It’s a heartbreaking story about the violence of colonization and the history of Australia. But it’s also a story about one woman’s love of her family and homeland, and her fierce determination never to forget who she is or where she comes from.

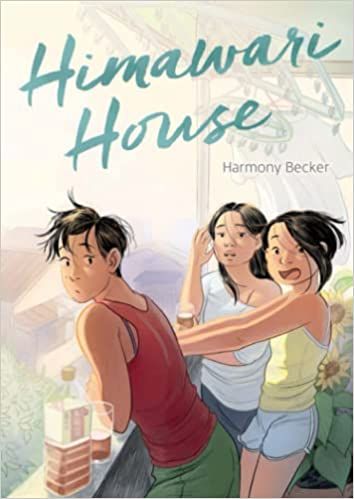

Himawari House by Harmony Becker (Korean, Japanese)

This YA graphic novel is about three foreign exchange students living in Tokyo. Nao, hoping to reconnect with her Japanese heritage, decides to spend the year studying Japanese. She moves into a house with two other exchange students, one from Korea and one from Singapore, and soon the three of them become close. It’s a slice-of-life coming-of-age story about friendship, language, and muddling through what it means to belong.

Mango, Mambo, and Murder by Raquel V. Reyes (Spanish)

This cozy mystery stars Miriam, a Cuban American food anthropologist whose move back to Miami leads to all sorts of trouble. Just when she’s landed a fantastic gig as a cooking expert on a Spanish morning TV show, people in the food world start dropping dead — and it’s not long before Miriam finds herself hip-deep in the investigation. This book is full of mouthwatering food descriptions, lots of family drama, and loads of Spanish.

The Henna Wars by Adiba Jaigirdar (Portuguese)

This YA romance is strikes the perfect balance: it’s a serious and heartfelt story that addresses racism and homophobia head-on, but it’s also bursting with joy. Nishat is a Bengali Irish teenager who’s just come out and is struggling to figure out how to live as her authentic self in a world that seems to confine her to boxes. Things get even more complicated when she falls for Flávia — her rival in a school business competition.

True Biz by Sara Nović (April 5th) (American Sign Language)

While this novel does contain a lot of translated ASL conversations, it is also full of untranslated ASL — or, at least, as untranslated as written/visual representations of a visual, moving language can be. Set at a fictional school for the Deaf in a small town in Ohio, it follows the interconnected lives of several students and teachers over the course of one tumultuous year. Bursting with life and language, it’s at once a love story, a family drama, a coming-of-age novel, and a fierce call-to-action.

Translation is such a complicated and messy act. A work of translation can be a bridge, an opening, a doorway into a different world or culture or language. But translation is also a reminder that there is only so much that is transferable. Rioter Nicole Froio wrote a gorgeous piece about translation, culture, English language privilege, and the things that can’t be said — I highly recommend giving it a read. I know I’ll be thinking about it when I pick up some of these 2021 books in translation, and these 2022 books in translation.