My relationship with Japanese literature is fairly new. I discovered it last year after India went into a lockdown. I was stuck in a lonely city away from friends and family, and needless to add here, it was a difficult phase. This is when I came across this genre, and frankly it changed my perception of the world and myself. The rich vocabulary yet the simplicity of the prose and the choice of words in Japanese fiction displayed a refined sensitivity of expression that left me with a lot of hope. The characters felt very close to home and their everyday struggles became mine. The rumination on love, loneliness, and hope beating all odds made it all the more appealing to me. When the world was going through a humanitarian crisis, I found immense comfort in the pages of Japanese fiction where life included but was not confined to diseases, death, and decay.

Love In The Unlikeliest Of Places

In Yoko Ogawa’s The Housekeeper And The Professor (translated by Stephen Snyder), we see a housekeeper and her son finding companionship and tenderness in a math professor. The housekeeper had to reintroduce herself to him every day as after a traumatic accident, the professor couldn’t remember anything past 1975 for longer than about 80 minutes. When he discovered, over and over, that she had a son, he urged her to bring him to his house as he didn’t want him to be alone after school. He fondly called the child “Root,” because he felt the boy’s flat haircut resembled the square root sign. Their common love for baseball brought the man and the boy closer.

As the housekeeper grew more and more drawn to the professor, realizing that he was a man worthy of patience, dignity, and kindness — emotional needs that were left unmet by the previous housekeepers — she also learned to look at everything around her with a newfound sense of awe. The professor’s entire life banked on numbers, and numbers are how he connected with the housekeeper and Root.

Though this is not a love story, this story is definitely of love. The housekeeper found herself fully in love with the professor’s fascinating mind and in turn with mathematics. The more love she cultivated for the professor, the more full of life and wonder she became about herself and the people and the world around her. His presence in her life didn’t fit into the common tropes of a lover or a father/brother figure. Much to the disbelief of his sister-in-law, all they shared was a deep, intense friendship that was too sui generis to fit into conventional boxes.

Love As Hope

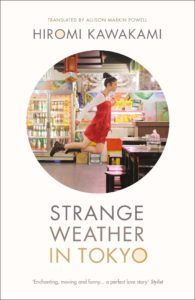

In Hiromi Kawakami’s Strange Weather In Tokyo (translated by Allison Markin Powell), Tsukiko and her sensei’s life-affirming love story is one for the ages. She was in her late 30s and he was at least 30 years her senior. They kept bumping into each other. One thing led to another and what started with sharing food and drinks eventually metamorphosed into hesitant but easy intimacy and finally love.

The end of World War II saw a global shift in culture, technology, and how humanity operated in the world they inhabited. Japan previously a place brimming with cultural richness fell prey to the mechanical and technology-based lifestyle of the post-war world. This is where lies the success of this novel, as it reminds us of all the tenderness the world still has to offer in an age of long work hours and dull business suits. This book is a celebration of love and friendship and how humanity forges bonds with the “other” to keep the “self” going.

Tsukiko struggled with her feelings for Sensei. She was a true introvert who reflected on her personality often. This aspect of the novel would easily help the reader develop intimacy with her, the kind of intimacy that is very hard to represent in fiction as short and well-paced as this one. The author hasn’t spent any time discussing her job, as it was unimportant. Here, interpersonal relationships matter more than the drudgeries of everyday life and what individuals do to sustain themselves. There is no surprise factor in this book, and this is what makes it all the more enjoyable, as sometimes the most beautiful days are the ones where nothing of significance happens. Powell has weaved together all the wonderful insignificance the world has to offer in the form of human relationships and how that becomes the life force in a world torn by hate, bloodshed, and wars.

Our world doesn’t always feel like a habitable place. But at least we’ll have our Japanese fictional counterparts to share our woes with. And in times of despair, solidarity — albeit from fictional people — can be a source of infinite comfort and joy. If you’d like to experience more of this genre, please check out Exploring Japan Through 6 Books and 14 Must-Read Japanese Books Available In English Translation.

Source : How Does Japanese Literature Portray Tenderness Towards The “Self” And The “Other”?