Pink Noise

In 1951, experimental composer John Cage entered an anechoic chamber at Harvard University. The room was small, with walls covered in foam pyramids, and designed to be totally silent. But when John Cage went inside he heard two tones: one high, one low. Afterwards he asked his guide what the tones were and he was told that one was the sound of his blood, the other the sound of his nervous system.

No one stays in an anechoic chamber for long. It’s said that if you do you lose your shit. Complete silence can induce nausea, claustrophobia: it’s a loud and unwelcome look inward, for many, an inability to tolerate what echoes inside one’s own body.

A few years before my daughter is born, my ears begin to ring and won’t stop: a playable note twinned with the high-end whine of an old TV. At first, I can only find relief with my cheek pressed against the refrigerator. Its low electrical ohm-ing fills all the spaces so my tones become two stones in a solid wall, which is its own form of silence.

A doctor warns me that the volume could rise in pregnancy, something about hormones, but instead the sounds, and the fear, both lessen. I’m a vessel now, an adaptable structure, a ship that, through some ancient, mystical process, can build itself as it sails across the ocean.

In the first year of my daughter’s life the sound roars back, waxing and waning with my changing moods, quieting for days and then demanding attention, like a bone broken in childhood acting up when it rains.

It is during this time that the quietest room in New York City arrives on the top floor of the Guggenheim Museum. It’s not an actual anechoic chamber, but a “semi-anechoic chamber.” Training wheels for insanity, I tell my partner. We buy tickets.

We remove our shoes before entering. No phones allowed. We shed our possessions. We agree not to speak. We pass through a room between two heavy doors as if prepping in airlock before a space walk.

Like John Cage, we have a guide, a delicate-looking man with wire-rimmed glasses.

He tells us Doug Wheeler created this room, named it PSAD Synthetic Desert III. Wheeler first had the idea for it in the ‘60s, so long ago he can’t remember what PSAD stands for. Also, as far as anyone knows, there was never a I or a II. Wheeler learned to fly from his pilot parents, grew up in the Arizona mountains.

I wonder, listening, how it might’ve altered me to live in wild spaces, instead of the world’s first suburbs, then the world’s most examined city. Doug Wheeler thought to himself, after landing his prop plane on a dry lakebed in the Mojave, waiting for the “tink-tinking” of its engine to die down: “I’m hearing distance. I’m seeing distance.”

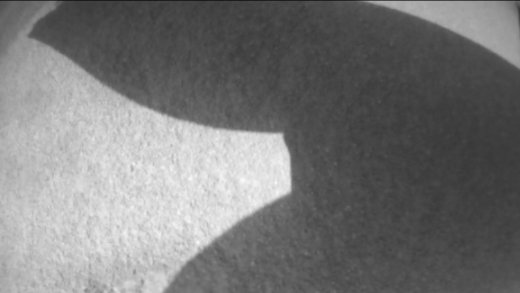

We advance, five in total, to our final destination, our synthetic desert, our semi-anechoic home for the next fifteen minutes. We sit on a white platform surrounded on three sides by a forest of white fiberglass pyramids, seen from above. Maybe it’s the feeling of standing on the edge of something, but the view seems vast in this smallish room, the gray-lit peaks both spiky and soft. I could see someone saying they looked like rows of shark’s teeth, if that person were afraid. But I’m not afraid.

The five of us have nothing to fear: we will not lose our minds in the fiberglass forest because we’re being protected by pink noise, pumped in by Wheeler.

The pink noise here is desert wind, but pink noise is also the pattern of hearts beating, the hush of far-off traffic, a fan’s oscillation, interstellar gases light years away, hissing as they approach a black hole.

A sound like the color inside a shell, an ear-shaped hollow for hot secrets, the color of everyone’s first home inside a mother. Am I getting to vaginas? Who isn’t, ever? It’s the only way out for so many of us, though not my daughter. My daughter was airlifted, rescued. Her pink noise heartbeat was losing its color. She had inched too close to the black hole.

The most notable thing about the quiet room is that everything in it that is not itself sounds very, very loud. My own ears: deafening, five-alarm fire. Every pants-swish or footstep a record scratch that halts the whole world’s turning, makes you whip your head around to discern its source. We walk slowly, make small movements. We peer over the edge of the platform at the landscape of triangles: look up, look around.

At some point everyone sinks to sitting. At some point, we all lie down. At some point, the guide takes off his glasses and it’s the loudest sound I’ve ever heard, like a million people tearing apart the sealed flaps of a million cardboard boxes. He curls himself into a fetal position and rests on the floor with the rest of us. He closes his eyes and I can hear my heart breaking: we are all so safe and vulnerable here, so brittle outside in the loud world. When my stomach rumbles a few minutes later, everyone feels the earthquake.

I wonder if they sometimes return to this room in their minds, like I do. I wonder if they were hungry, too.

The post What She Heard in a Room Without Sound appeared first on Electric Literature.