My history with “New Adult” (NA) books goes way back. As a first-generation college student from a very small high school staring down a large University before the turn of the millennium, I read at least 22 volumes of Sweet Valley University in preparation. I asked my school and Navy base librarian for more books set in college, but this was all they could find besides one random volume of Freshman Dorm. Thus began my journey of wishing there were more books for people making the journey into adulthood. Some people may not consider the SVU books to be true NA, but I would argue they capture the purpose of it, albeit constrained by early ’90s mainstream sensibilities. SVU wasn’t the start of NA, but it was my personal beginning.

Obviously the hankering for and concept of these books has been around for a long time, but most people refer to a 2009 contest from St. Martin’s as the beginning of NA. They were seeking “cutting-edge fiction with protagonists who are slightly older than YA…fiction similar to YA that can be published and marketed as adult — a sort of an older YA or new adult.” This, at least, started the conversation in earnest in the publishing industry.

“I remember thinking ‘Oh, well obviously this makes sense as a category.’,” says blogger and editor Laura Helseth. “With YA exploding in popularity in the years before, it made sense that those readers wanted their stories to grow with them.”

Some industry folks were excited about the new category and thought it made as much sense as Helseth, while others were loudly negative about it. Personally, I was interested in writing NA, but so many agents repeatedly said “it is not a thing” that I was discouraged and never tried. However, I knew the claim that there was “no market for it,” must be false, because writers often write what they want to read. Many other writers felt the same, but some were braver than I. Indie authors, who are never afraid of trying new things, started writing and self-publishing NA.

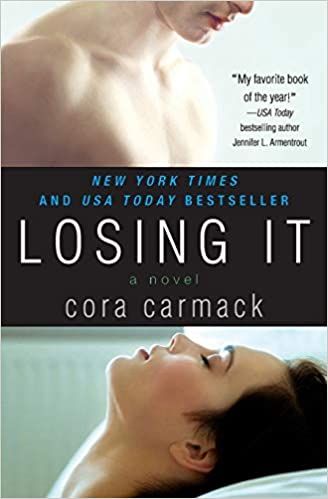

In 2011 and 2012 books like Cora Carmack’s Losing It and Tammara Webber’s Easy took off, which made romance publishers sit up and take notice. Several romance publishers started investing in NA in 2012, with even more joining in 2013. Also in 2013, the Book Industry Study Group created the BISAC designation, entering it into the globally-recognized system for categorizing books. In 2013, NA Alley, a website to support NA authors similar to the very popular YA Highway launched. By 2014, Publisher’s Weekly called new adult “a full-on phenomenon.”

So what happened? Why haven’t we seen NA break out as wildly as YA did? There aren’t any major awards or conventions or professional organizations devoted to new adult. NA Alley closed up shop in 2015. Many of the publishers absorbed their NA lines into their adult lines in the past couple years. A lot of publishing professionals are still saying “New Adult is not a thing.” We haven’t seen many breakout mainstream hits that we call NA (though there are some, but we call them something else).

This is my opinion based on my close observation and experience in the category of what happened and where we’re going. As for my experience in the category, I was the Publicity Director for Entangled’s New Adult imprint Embrace in 2013 and 2014, I hosted a popular NA pitch contest in 2012, and I selected what would become Jennifer Blackwood’s Unethical to mentor in Pitch Wars in 2013.

The first several big NA books were sexy romance and erotica. They were often called “YA romance with sex.” Fifty Shades of Grey featured a college-aged protagonist. This led people to start thinking of new adult not as a category that encompasses all genres (like young adult, which can have horror, science fiction, romance, fantasy, literary, etc.) but as a sub-genre of romance. NA advocates say it’s poised to break out of that mold, but we were all saying the same thing in 2011. I still hope it does, but I’m far less confident NA will be able to shake this stigma. I would be thrilled to be proven wrong.

Booksellers and librarians as a whole did not embrace the genre, with several articles and blog posts being published calling the category a marketing ploy. It should be noted that all category and genre classifications are essentially marketing-driven. See: every discussion about literary science-fiction novels about whether they are science-fiction or literary. Adding to the complications, “New Adult” was already a section in most bookstores: for new releases in Adult fiction. In my perfect world, we would be able to rename Young Adult “Teen Fiction” and NA “Young Adult,” but there’s zero chance of that happening at this point.

Some argue that adding NA is further slicing books up into stringent age categories, and that’s a valid concern. Age is a sliding scale spectrum and trying to set hard section markers is difficult. Industry folks are always trying to figure out exactly where the line is between upper middle grade and lower YA, for example. Many times, it could go either way because people and their experiences are not as easily placed into such clean categories as bookstores are.

New adult is actually a pretty thriving category, but not in the traditional publishing world, where it’s largely considered a failed experiment. (An experiment I would argue was performed in the most unfavorable conditions.) Indie authors continue to publish and make excellent money on NA books. Rebecca Christiansen, author of Maybe in Paris and Wattpad Star, pointed out that NA romance thrives on Wattpad, as well as other online platforms. She said that Wattpad pursues NA stories for their Paid Stories program. It appears to be very popular on TikTok, which makes sense when you consider the platform’s core audience.

And there have been some extremely popular NA books published by traditional publishers — they’re just usually called something else. In my opinion, Lev Grossman’s The Magicians is quintessential new adult, but he calls it adult fantasy. He said he wanted to write something like Narnia or Harry Potter “but written for adults…with all the sex and drinking and other complicated adult realities that young adult authors have to leave out.” YA books set in college, such as Fangirl by Rainbow Rowell, Nina LaCour’s brilliant We Are Okay, Fresh by Margot Wood, and many more could easily be classified as NA. I recently read Tracy Deonn’s Legendborn, thinking the entire time that this was what I always wanted from new adult. Casey McQuiston’s wildly popular Red, White & Royal Blue is shelved as adult, often mistaken for young adult, and very clearly new adult.

It unfortunately makes sense for publishers to classify these books for adult or young adult shelves and market them as crossovers, because there are no new adult shelves in bookstores or sections in major book review publications. Author Jamie Beth Cohen, author of Wasted Pretty, told me her next book Liminal Summer “is what new adult is supposed to be, but it’s being categorized as women’s fiction because NA is so hard to market. I think maybe the publishing categories as they exist just don’t make sense anymore.”

The future of the new adult category is uncertain, but in my dream world it would become as varied and popular as young adult. We all know that teens tend to “read up” in age, preferring protagonists about two years older than them, so NA would be a great opportunity for them to safely explore what’s on the horizon like I did with SVU, as well as for younger adults to read books featuring characters in similar stages of life. My guess is that NA books will continue to be absorbed into the edges of YA and adult fiction, then marketed as “crossovers” but I beg publishing to prove me wrong.

Source : The History and Future of New Adult